In my years of shooting film, I’ve stumbled across some great gadgets built for film photography that can be used in digital photography. My color correction filter pack is one of them.

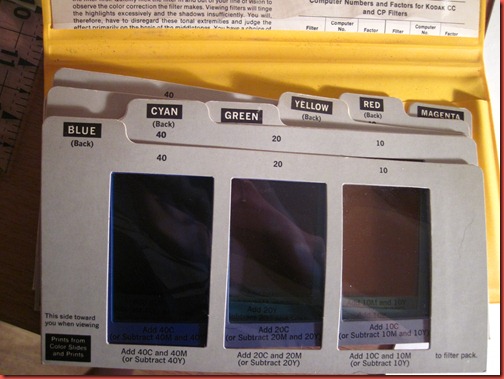

They come in a whole pack with both CMY and RGB filters, each with their own gradient. The purpose of these was originally to help with color correction in a darkroom (color darkroom printing post coming soon, so you’ll see what I mean).

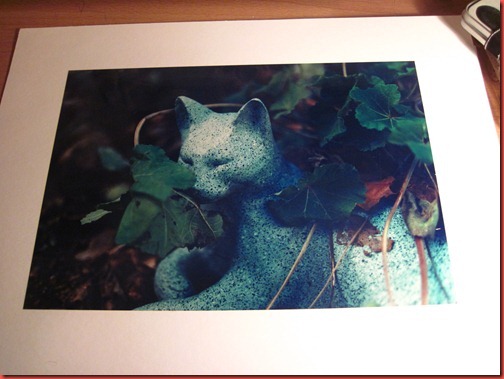

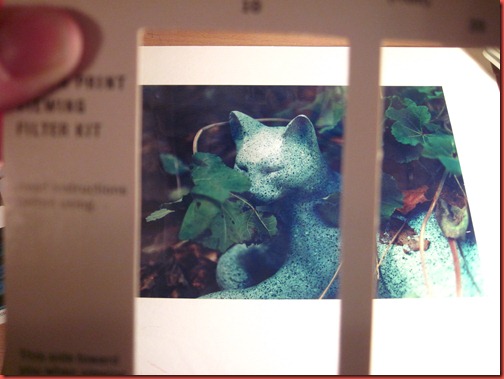

Example, here’s a color print I hand processed in my color darkroom. I love it, and if you follow my color film photography you know I often add a color cast to photos. In this case, I added a hint of blue.

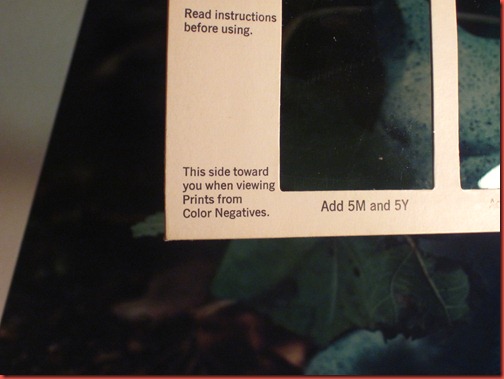

These are simple enough to use. Pick the color that is opposite to the color you think you’ve made a mistake with (so for blue cast, I’d grab yellow). Look through the various viewing windows until the colors look right to you, then read the box below to see how to correct this in a darkroom enlarger.

Here’s when we view the photo through a yellow filter. The blue cast is corrected.

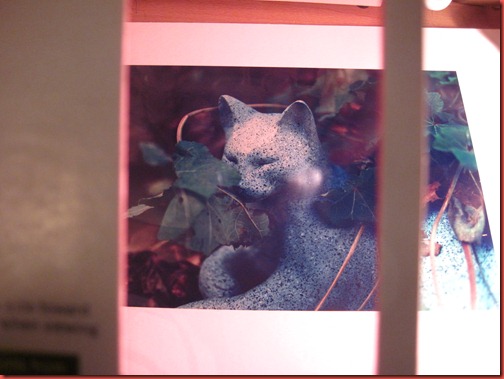

Here’s when we look through a magenta filter. It’s pretty easy to tell that we don’t need any additional magenta in this photo.

So, that’s pretty much it for film. Just keep looking through squares until it looks right, make the suggested adjustments and run your next print through.

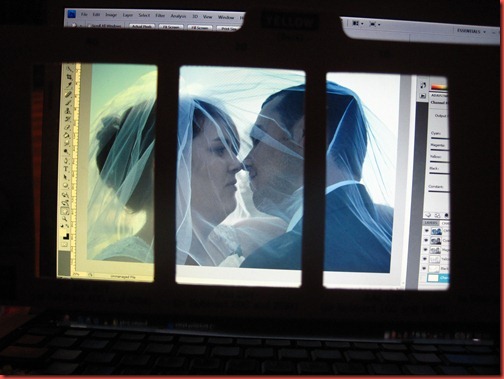

Now, how can we apply this to digital? Here’s a SOOC shot I took at a wedding. It has a cyan/blue cast that I don’t like. Let’s use the filters and see what could work better.

I held the yellow filter card up to the screen and we can see that the middle filter is the closest to correcting the color. The left is too yellow, and the right is too blue.

So, how is this more useful that just using Photoshop tools? Sometimes it’s not. The white balance auto-correct in camera raw works well a lot of the time, and you can eye your colors using a lot of the color correction tools built in. Why this is handy is because camera raw doesn’t always get a perfect white balance. Also, this gives you a starting guide with color correction without having to wait for actions to process or having to use the history button.

The only drawback I’ve found is that color correction units (which the cards use) don’t currently translate to Photoshop CS4. While doing a quick Google search, I found there are plug-ins you can get which will translate color correction units to Photoshop. In the meantime, I think this at least provides us with a shortcut and an idea of where we’re going.

Happy editing!

Kelly